The Marginalian has a free Sunday digest of the week's most mind-broadening and heart-lifting reflections spanning art, science, poetry, philosophy, and other tendrils of our search for truth, beauty, meaning, and creative vitality. Here's an example. Like? Claim yours:

Also: Because The Marginalian is well into its second decade and because I write primarily about ideas of timeless nourishment, each Wednesday I dive into the archive and resurface from among the thousands of essays one worth resavoring. Subscribe to this free midweek pick-me-up for heart, mind, and spirit below — it is separate from the standard Sunday digest of new pieces:

Letters to Susan Gilbert" width="320" height="168" />

Letters to Susan Gilbert" width="320" height="168" />

The commencement address is a special kind of modern communication art, and its greatest masterpieces tend to either become a book — take, for instance, David Foster Wallace on the meaning of life, Neil Gaiman on the resilience of the creative spirit, Ann Patchett on storytelling and belonging, and Joseph Brodsky on winning the game of life — or have originated from a book, such as Debbie Millman on courage and the creative life. One of the greatest commencement speeches of all time, however, has an unusual story that flies in the face of both traditional trajectories.

In 2000, Villanova University invited Pulitzer-Prize-winning author, journalist, and New York Times op-ed columnist Anna Quindlen to deliver the annual commencement address. But once the announcement was made, a group of conservative students staged a protest against Quindlen’s strong liberal views. The commencement was cancelled. “I don’t think you should have to walk through demonstrators to get to your college commencement,” Quindlen lamented. Rather than retreat, however, she emailed the undelivered commencement address to a Villanova graduate student who had expressed disappointment at the situation. Years before the social web as we know it today, the speech spread like wildfire across the internet. A few months later, Quindlen expanded it into the short and lovely book A Short Guide to a Happy Life (public library).

I’ve never earned a doctorate, or even a master’s degree. I’m not an ethicist, or a philosopher, or an expert in any particular field… I can’t talk about the economy, or the universe, or academe, as academicians like to call where they work when they’re feeling kind of grand. I’m a novelist. My work is human nature. Real life is really all I know.

And know it she does:

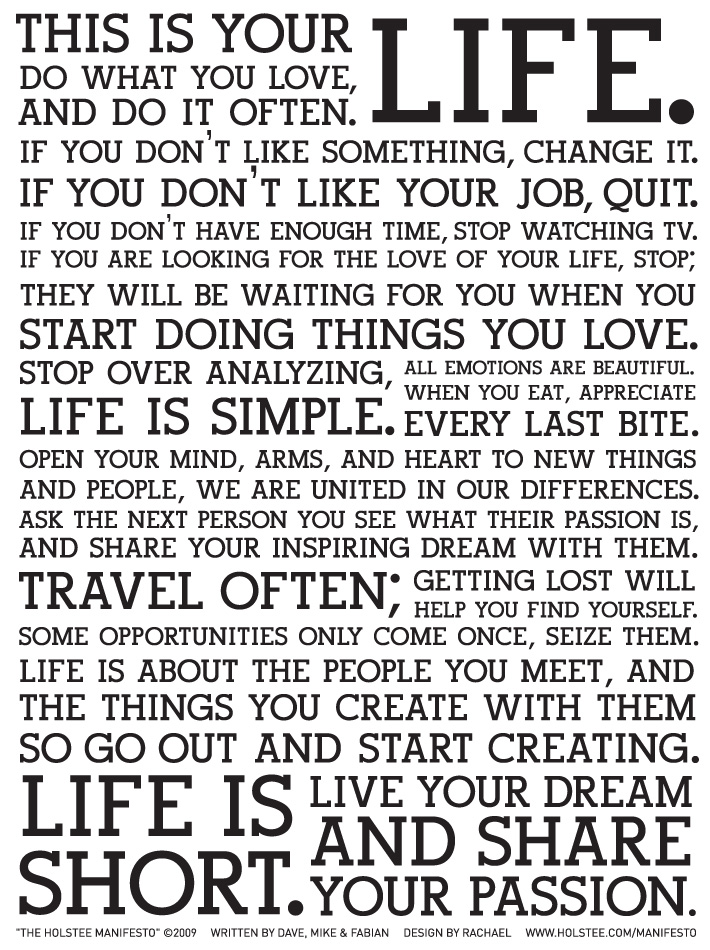

Don’t ever confuse the two, your life and your work. That’s what I have to say. The second is only a part of the first. Don’t ever forget what a friend once wrote to Senator Paul Tsongas when the senator had decided not to run for reelection because he’d been diagnosed with cancer: “No man ever said on his deathbed I wish I had spent more time at the office.”

Don’t ever forget the words on a postcard that my father sent me last year: “If you win the rat race, you’re still a rat.”

Quindlen considers the question of the self and what makes us who we are, what makes us worthy of being. And while the great Annie Dillard may have cautioned to not “ever use the word ‘soul,’ if possible,” it seems impossible to address the question of what makes a meaningful life without addressing the human soul, which Quindlen does beautifully:

There are thousands of people out there with the same degree you have; when you get a job, there will be thousands of people doing what you want to do for a living. But you are the only person alive who has sole custody of your life. Your particular life. Your entire life. Not just your life at a desk, or your life on the bus, or in the car, or at the computer. Not just the life of your mind, but the life of your heart. Not just your bank account, but your soul.

People don’t talk about the soul very much anymore. It’s so much easier to write a résumé than to craft a spirit. But a résumé is cold comfort on a winter night, or when you’re sad, or broke, or lonely, or when you’ve gotten back the chest X ray and it doesn’t look so good, or when the doctor writes “prognosis, poor.”

Even those trying to find their purpose, even those engaged in fulfilling work, and even those of us lucky enough to have no separation between “life” and “work,” can get consumed by our modern cult of productivity. Quindlen’s words come as a vital reminder of what matters, what counts, what the true aliveness of life is:

You cannot be really first-rate at your work if your work is all you are.

So I suppose the best piece of advice I could give anyone is pretty simple: get a life. A real life, not a manic pursuit of the next promotion, the bigger paycheck, the larger house. Do you think you’d care so very much about those things if you developed an aneurysm one afternoon, or found a lump in your breast while in the shower?

Get a life in which you notice the smell of salt water pushing itself on a breeze over the dunes, a life in which you stop and watch how a red-tailed hawk circles over a pond and a stand of pines. Get a life in which you pay attention to the baby as she scowls with concentration when she tries to pick up a Cheerio with her thumb and first finger.

Turn off your cell phone. Turn off your regular phone, for that matter. Keep still. Be present.

Get a life in which you are not alone. Find people you love, and who love you. And remember that love is not leisure, it is work.

Here, Annie Dillard, who so memorably expounded the power of presence over productivity in the making of a rich life, would have agreed. For Quindlen, however, an even richer life than that of simply being present is one of being present with a palpable generosity of spirit towards the world:

Get a life in which you are generous. Look around at the azaleas making fuchsia star bursts in spring; look at a full moon hanging silver in a black sky on a cold night. And realize that life is glorious, and that you have no business taking it for granted. Care so deeply about its goodness that you want to spread it around. Take the money you would have spent on beers in a bar and give it to charity. Work in a soup kitchen. Tutor a seventh-grader.

All of us want to do well. But if we do not do good, too, then doing well will never be enough.

Quindlen, who had a jarring confrontation with the mortality paradox early in life — at nineteen, she lost her mother to ovarian cancer and spent her sophomore year of college administering morphine while her peers partied — considers the Alan Wattsian idea that putting at rest our resistance to the inevitability of death liberates us to be more alive. (Sarah Lewis put this beautifully when she observed, “When we surrender to the fact of death, not the idea of it, we gain license to live more fully, to see life differently.”) Quindlen reflects on the tragedy that split her life into a “before” and an “after”:

It is so easy to waste our lives: our days, our hours, our minutes. It is so easy to take for granted the pale new growth on an evergreen, the sheen of the limestone on Fifth Avenue, the color of our kids’ eyes, the way the melody in a symphony rises and falls and disappears and rises again. It is so easy to exist instead of live. Unless you know there is a clock ticking.

[…]

“Before” and “after” for me was not just before my mother’s illness and after her death. It was the dividing line between seeing the world in black and white, and in Technicolor. The lights came on, for the darkest possible reason.

And I went back to school and I looked around at all the kids I knew who found it kind of a drag and who weren’t sure if they could really hack it and who thought life was a bummer. And I knew that I had undergone a sea change. Because I was never again going to be able to see life as anything except a great gift.

“We have entered a new age of fulfillment, in which the great dream is to trade up from money to meaning,” philosopher Roman Krznaric wrote in his fantastic manifesto for finding meaningful work, but Quindlen reminds us that the luxury of seeking fulfillment rather than mere survival came at a price — and yet how easily we take it for granted:

It’s ironic that we forget so often how wonderful life really is. We have more time than ever before to remember it. The men and women of generations past had to work long, long hours to support lots and lots of children in tiny, tiny houses. The women worked in factories and sweatshops and then at home, too, with two bosses, the one who paid them, and the one they were married to, who didn’t. . . . Our jobs take too much out of us and don’t pay enough.

Life is made up of moments, small pieces of glittering mica in a long stretch of gray cement. It would be wonderful if they came to us unsummoned, but particularly in lives as busy as the ones most of us lead now, that won’t happen. We have to teach ourselves how to make room for them, to love them, and to live, really live.

[…]

This is not a dress rehearsal, and that today is the only guarantee you get.

How, then, are we to fully inhabit the miracle of our existence, that cosmic accident by the grace of which we ended up alive, here, now? Quindlen offers a gateway to presence:

Consider the lilies of the field. Look at the fuzz on a baby’s ear. Read in the backyard with the sun on your face. Learn to be happy. And think of life as a terminal illness, because, if you do, you will live it with joy and passion, as it ought to be lived.

A Short Guide to a Happy Life is the kind of read that stays with you for a long time, the sort you revisit again and again when the ground beneath your feet shakes and you reach for a reminder of the solid center. Complement it with more fantastic commencement addresses by Bill Watterson, Joss Whedon, Oprah Winfrey, Ellen DeGeneres, Jacqueline Novogratz, Aaron Sorkin, Barack Obama, Ray Bradbury, J. K. Rowling, Steve Jobs, Robert Krulwich, Meryl Streep, and Jeff Bezos

Every month, I spend hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars keeping The Marginalian going. For seventeen years, it has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, not even an assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider aiding its sustenance with a one-time or loyal donation. Your support makes all the difference.